Shaurya Thapa on how a symbol of resistance went on to become one of the most invoked images of hyper nationalism

The Supreme Court recently stated that a plea to change India’s name officially to Bharat be converted into a representation and forwarded to the Union government instead for a decision. Chief Justice of India, Sharad. A.Bobde said that, “Bharat and India are both names given in the Constitution. India is already called Bharat in the Constitution. According to the petitioner called Namah, there should only be one name for a country. While speaking to ANI he said that, “the name should be uniform. One voice, one nation, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi says.”

From literature, to cinema, to slogans ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, India’s visual representation as a mother has undergone many transitions since the previous century. While initially she was a secular entity, she has now easily become one of the most invoked symbols of hyper-nationalism and Hindu extremism. It’s only ironic that at one point of the freedom struggle, the image of Bharat Mata was supposed to unite the diverse communities of the British colony under one secular umbrella.

Even though she’s presented in the media with a largely Hindu aesthetic, this is a recent phenomenon. Historian and ex-Chairman of Delhi University’s Department of History, Dwijendra Narayan Jha says, “Far from being eternal, Bharat mata is little more than 100 years old. Insistence on her inhabitants forming a nation in ancient times is sophistry. It legitimatises the Hindutva perception of Indian national identity as located in remote antiquity, accords centrality to the supposed primordiality of Hinduism and spawns Hindu cultural nationalism.”

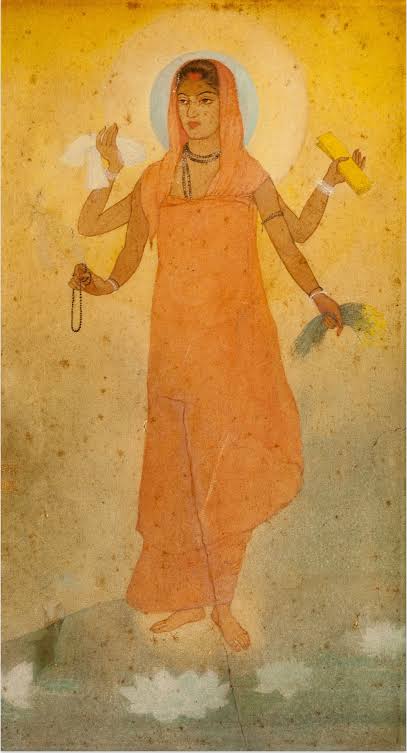

Shobha Singh: Bharat Mata (c. 1947). Source: Neumayer and Schelberger

In the same vein as Jha, some historians speculate that, as an idea Bharat Mata might have been born back in the 1800s. In the form of written word, she made her debut in a 1873 play called Bharat Mata, written by Kiran Chandra Bannerjee. The plot involves a husband and a wife finding a temple dedicated to mother India in a forest which inspires them to start a rebellion against the British.

The very fact that she’s found in a temple indicates a Hindu element to Bharat Mata, equating her to one of the many mother goddesses in Hinduism. However, we also need to note that this was the time when there was no uniform concept of Hinduism (it still remains to have very diverse and disparate sects and forms of worship) and it was the British who tried institutionalising it as a religion. Still as mentioned before, the presence of a temple added a ‘Hindu’ or ‘Sanskritic’ connotation to the Mother.

But another Bengali novelist Bankim Chandra Chatterjee tried to counter this portrayal with a secular outlook. The British cartographers had made a rough outline map of the Indian subcontinent by the late 19th century. In Chatterjee’s magnum opus, Anandamath, he uses this image of the motherland to signify Mother India. This novel also mentions the song Vande Mataram, the title of which roughly translates to ‘I praise thee, Mother’. “A mother-like figure for Chatterjee was initially represented as Mother Bengal (Banga Mata). But it was Rabindranath Tagore in the 1896 Congress session who sang the song Vande Mataram for the first time, and accorded a national character to the motherly figure mentioned in the song,” says, Richa Raj, associate professor for history in Delhi University’s Jesus and Mary College.

In the Swadeshi movement in the 1900s, the following around Mother India increased. She came to represent a mother for the Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis, Buddhists, and various other religions alike. The feeling of being an ‘Indian’ arose through such nationalism and Indians had someone to fight the British for; they had to protect their Mother.

And then the Mother adopted one particular religion.

There has been no mention of any Bharat Mata in any of the Vedas, Puranas, Gita or any other ancient literary work associated with Hinduism. And yet, Hindus started reclaiming this so-called nationalistic mother as a mother of Hindus. Raj says, “while Hindu cultural nationalism attempted to present her as a Hindu deity, equivalent of Durga or Kali, other factions tried to give her a secular identity.”

For instance, even though Vande Mataram had become a popular patriotic anthem and a hymn to the Mother, Subhash Chandra Bose who served as President of the Congress for 1938-39 was bothered by it. What troubled him was that, while the first verse seemed to be dedicated to Mother India, the last verse indicated an invocation of the goddess Durga. This was in contrast to the secular, multicultural picture that the Congress was painting for itself. The very fact that this song had been taken from Anandamath was also problematic. The novel after all, pits Hindu protagonists against an army of Muslim adversaries.

Bose took the matter forward to Rabindranath Tagore for further advice. Tagore along with other leaders of the INC like Maulana Azad felt that adopting the entire composition as a national song would not be a wise decision as it would offend non-Hindus. As a result, only particular verses of the song were taken and declared as the national song of the country after attaining independence. Till date, the version of Vande Mataram which is sung all across India is this edited one.

In terms of aesthetics, it was Rabindranath’s nephew Abanindranath Tagore who gave this Mother an image of a proper goddess. Tagore was a painter known for bringing swadesi values to Indian art, rather than blatantly copying European styles. One of his most iconic works remains to be the watercolour painting once again titled Bharat Mata.

Abanindranath Tagore, Bharat Mata

While Abanindranath’s vision of the Mother is Hindu in nature, he still gave her an ascetic look, which was a far cry from the opulent figures of Hindu mythology. Clad in saffron robes, she is shown as having four hands. In each hand, she holds symbolic paraphernalia — a book representing knowledge, a rosary bead representing spirituality, sheaves of paddy representing agriculture, and a white cloth which maybe symbolizes peace (the meaning of these elements have undergone various interpretations).

It was painted in the year 1905, which gives us more context behind its relevance. This was the same year when the partition of Bengal was initiated under Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India. The people of India were raging with anger and this gave birth to the Swadesi movement when Indians burnt British manufactured-goods in large assemblies.

The freedom movement received a resurgence as Tagore’s painting garnered a cult status. “I would reprint- it, if I could, by tens of thousands, and scatter it broadcast over the land, till there was not a peasant’s cottage, or a craftsman’s hut, between Kedar Nath and Cape Comorin, that had not this presentment of Bharat-Mata somewhere on its walls,” sister Nivedata, a teacher and disciple of Swami Vivekananda wrote in her journal.

Interestingly, it has also been said that Nivedata was the inspiration behind the central figure of the painting. Even though she spent most of her spiritual life in India, she was born in Northern Ireland. So the great irony is that, technically a woman from the United Kingdom inspired India’s most important personification.

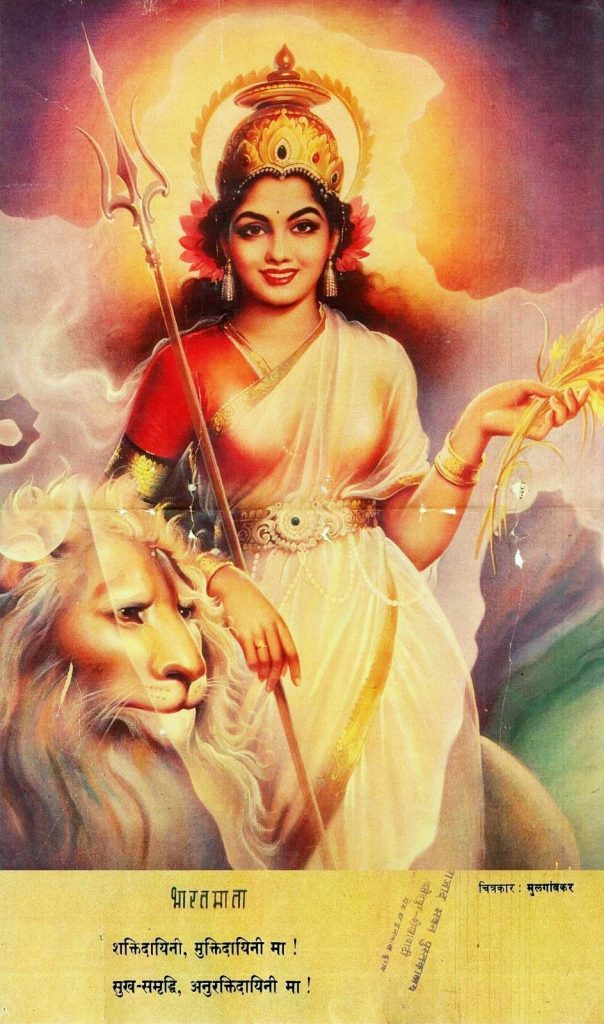

But the mendicant-like simplistic look didn’t stay for long, as from the early 20th century till present day, Bharat Mata began to be presented as a more radiant and decorated goddess. In most of the paintings, she was described as wearing a saree, and a crown, sometimes holding the national flag or a trishul (trident).

VD Savarkar in the 1920s proudly began to proclaim her as a Hindu icon and called for the rule of Hindutva which obviously triggered many debates like it does to this date. Savarkar’s pamphlets and other writings expose his desire to create a free Indian state where the hegemony of the Hindus would exist. Such writings wrongly equate the Indic civilization with the Hindu civilization. One should note that the word Hindustan itself never represented a Hindu nation. The word Hindu in itself was a reiteration of the word ‘Indus’ as India was the land of the river Indus (which was called Sindhu in Sanskrit) for many foreign travelers like Al-Beruni.

In Who Is A Hindu?, Savarakar included all the religions of India under the label of Hinduism and called for fighting not just for swades but an Akhand Bharat (Undivided India). An Akhand Bharat would include the entire subcontinent under a unified Hindu wave, under the Hindu culture. Bharat Mata started becoming a representative of this Akhand Bharat. The Hindu visual elements in her images made more sense now.

As journalist Swapan Dasgupta writes in his latest book Awakening Bharat Mata, “the manifestations of nationalist conservatism were, under the circumstances, likely to be different. In pre-independence India there was a larger focus on custom, culture, religion and national pride than on political and state institutions.”

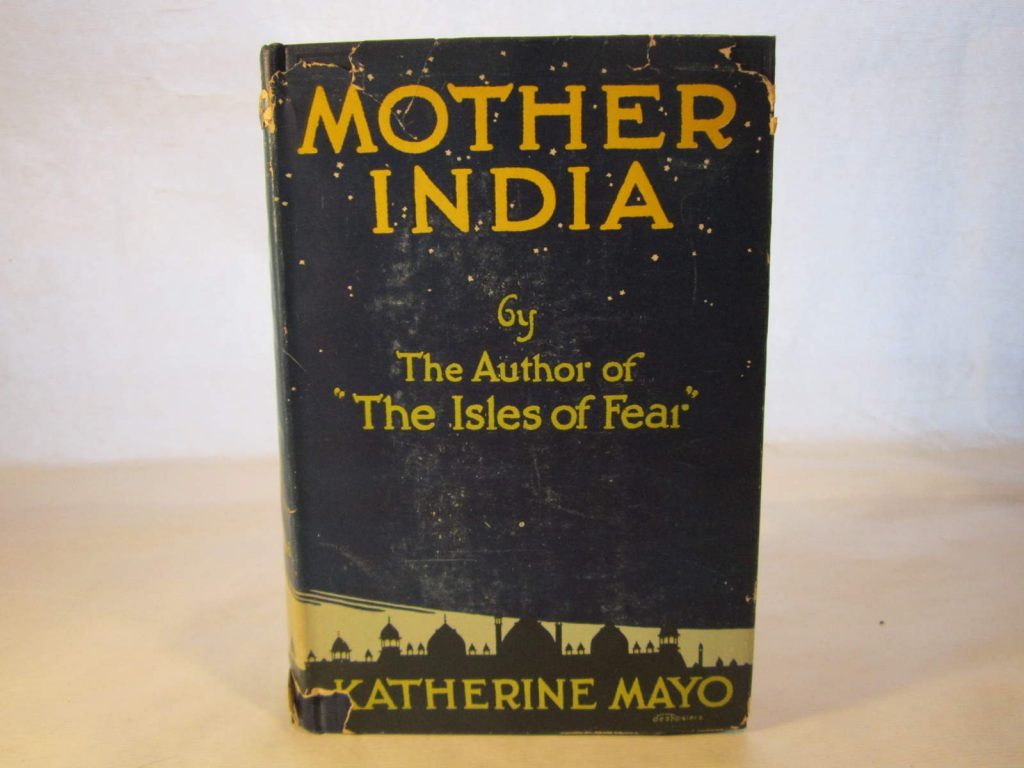

Around the same decade as Savarkar’s rise, another interpretation was brewing in another part of the world. American historian Katherine Mayo authored a book in 1927 titled Mother India, in which she presented aggressive claims criticising the Independence movement in India. While Mayo’s views have been outdated and extremist, some of her observations on marriage of young girls, untouchability and the caste system were strikingly real.

Katherine Mayo’s book presented aggressive claims against the independence of India

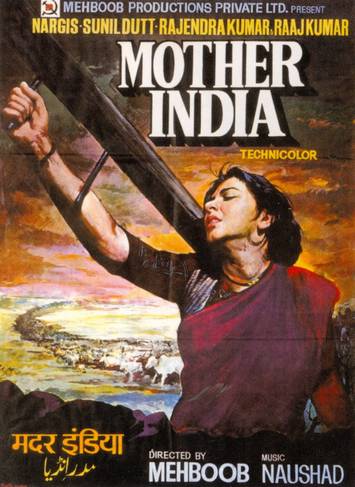

Needless to say, Indians and mostly Hindus were angered by this book. Effigies of Mayo and the book were burnt. Despite many angry pamphlets and books written in response to Mayo’s work, a movie released in independent India a few decades later provided retaliation for the Mother. Just from its poster, one can understand the immense impact that the Nargis and Sunil Dutt-starrer Mother India (1957) has had on Indian cinema. The lead character Radha raises her two sons in the absence of her husband, tills her own field and braves the vices of a scheming money-lender.

She is supposed to represent the idealistic Indian woman who is the epitome of the motherhood, just like how our country’s mother would be. The very fact that Radha survives without her husband (a bold plot point as women in Indian films have historically been reduced to submissive roles) is somewhat symbolic of how a new India is finally surviving on its own without its colonial master.

Director Mehboob Khan kept this title of the film on purpose, so that it’s remembered as a proud symbol of Indianness, rather than the name of a biased American book. Mother India went on to become the first Indian film to ever get nominated for an Academy Award For Best Foreign Language Film. While Nargis’s Radha added to the myth of Mother India, it also expanded the debates on Indian feminism. Is the ideal Indian woman ideal only when she’s being a good mother, a good wife, or a good daughter? Are family and household the only two aspects of our mother’s life?

The director Mehboob Khan named the film after Mayo’s controversial book to reclaim the word Mother India

Kousik Adhikari, a research scholar in English critiques Mother India with the following interpretation. “Indian films like the hegemonic Hindu society also follow Manu’s dictum that women should be governed in their childhood by their father, as a wife by her husband and in old age by their son. Mehboob Khan in his Mother India singularly follows this dictum revealing the ideal characteristic of a mother. After her husband’s leaving, she still hopes for his return and raises her children, sacrificing everything.”

The feminist perspective on Bharat Mata as an entity can be further seen through paintings and prints, as Raj notes. “Most of the art around Mother India shows her in a submissive state, needing rescue. There is a painting for example, when Bhagat Singh offers the Mother his own head. Such artworks in a way, encouraged the “sons of the soil” to give up their lives for this mother. All this evoked a sense of self-sacrifice among men as it was mostly brave men being depicted to sacrifice themselves for the motherland.”

Another leading feminist view-point on Bharat Mata comes from historian Romila Thapar, who points out how more than nationalism, Bharat Mata has always a symbol of Indian patriarchal society. “It must be said here that ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ is not an attribute of patriotism, but of deep patriarchy. Extreme mother-love is a camouflage for extreme misogyny,” she writes. The rise in sexual harassment and rape cases, she adds, show that, “there is no evidence to prove that devotion towards an abstract Bharat Mata translates into even a semblance of affection or respect for real flesh-and-blood women.”

Apart from interpretations in art, literature, and cinema, another lesser-known aspect in the presentation of Bharat Mata is the presence of Bharat Mata temples. The first such temple was constructed in 1936 in Varanasi and inaugurated by Mahatma Gandhi. The shrine doesn’t feature any idol of a goddess but a map of India in marble.

The Bharat Mata temple in Varanasi

Another significant temple was constructed in 1983 under the Vishva Hindu Parishad. This variant however features an idol of Bharat Mata, holding sheaves of grain in one hand, and an urn of milk in the other. According to Sadan Jha, associate professor, Centre for Social Studies, Gujarat, this idol apart from being devotional in nature is indicative of the Green Revolution and White Revolution which India needed at that time. “I look at these two temples as a process of the institutionalisation of a particular form of nationalism. These shrines to Bharat Mata frame not merely the gaze of onlookers (as do posters and popular prints) but make claims over the entire body of the visitor,” he explains this by saying that an act of going to a temple is a transformative act, “the human body is, potentially at least, transformed into the body of a devotee. This transformative characteristic has sufficient ability to change the nature of the icon, Bharat Mata itself.”

Mohan Bhagwat delivers a speech against the backdrop of Bharat Ma

Once Bharat Mata used to be printed on images alongside freedom fighters like the secular Mahatma Gandhi and the atheist Bhagat Singh. But now, she has been saffronised, just like how Savarkar might have wanted. Due to her increasing far right appropriation, not all Indians choose to proclaim their nationality by paying allegiance to Bharat Mata. But obviously, this is an easy parameter for Hindu extremists to classify them as anti-nationals. In 2016, RSS bigwig Mohan Bhagwat said it is important to create an India where people voluntarily say ‘Bharat Mata ki jai’ and going by the current scenario, that day might not be far off.