Suyash Verma on the complicated relationship between the brutal police lathi of today and the colonial act of whipping for misdemeanours

The recent reports of police brutality have raised concerns over the flouting of human rights. A man in West Bengal was allegedly beaten and died due to the strict measures resorted by the police amid the nationwide lockdown. Prime Minister Modi himself accepted the severity of such crackdowns by admitting that the lockdown has been “harsh” on people. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, requested the countries to restrain the misuse of force from under the garb of emergency measures. On the other hand, the Supreme Court of India dismissed the plea for establishing guidelines to keep law-enforcing authorities at check during the lockdown period. In such pretext, it is difficult to conclude that the events unfolding in India are worthy of a civilised nation.

While punishment is an instrument of authority, its abuse is deeply rooted in the nature of authoritarian states. The act of quelling a misinformed crowd has found its echoes in the history of this country’s making, and the infamous Jaliawala Bagh incident is a reminder of the same. Colonial enterprises strictly adhered to the principles of corporal punishment and its public exhibition. One might find such instances reoccurring during the current lockdown, where people are mercilessly roughed up and filmed by authorities in charge . The horror is then broadcasted through videos and pictures circulated on WhatsApp groups. It is a matter of profound regret that this show of dominance and the sadistic nature of punishment has left a stain in the reputation of law enforcement authority of India.

The slippery slope of such brutal punishments found its parenting in the Whipping Act of 1864, which was put into effect four years after the enactment of Indian Penal Act. Although William Bentick had replaced whipping with imprisonment in 1834, it successfully found its way back to the penal machinery after the Revolt of 1857. The ambiguity on its jurisdiction and application was widely discussed and debated throughout its usage. On the one hand, legislative assemblies discussed in depth the numerical proportionality’s like the number of whips, the diameter of rattan and usage of cat-o-nine-tails for the punishment, and on the other hand, they worried about insufficiencies of the punishment which had failed to bring any change to the hardened criminals. But the most baffling fact is that it took us another ten years after the independence to rescind a punishment that ignored the penological reasoning behind such atavistic laws.

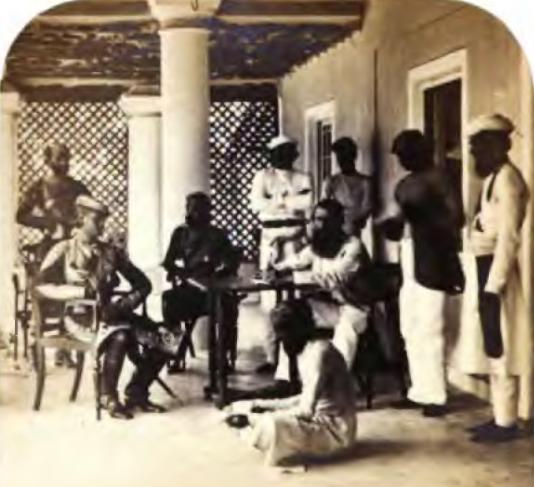

Commanding Officer of the Hyderabad Contingent (seated with beard), in the back-the police chief of Hyderabad

Whipping favoured the colonisers. It kept the prisons empty as the judge, jury, and the executioner were all played by the police. The Chief Commissioner of Oudh (now Awadh), Sir George Couper, expressed his delight by pointing out that the whipping bill had successfully counteracted the increase in the jail population, saving the government its maintenance cost. By the books, a magistrate sentenced the accused to whipping in the presence of an official-in-charge. But baton-friendly enforcers took delight in punishing the accused by themselves, often beating them to within an inch of their lives. The trend of punishment slowly and unconstitutionally skipped the legal procedure of its deliverance, becoming a quotidian affair and leaving people at the mercy of dishonest colonial police.

The sole purpose of the Whipping Act was to declare lashes as a complementary punishment for petty offences, but its modification also made it an ideal instrument for juvenile disciplining. The whipping law became a standard tool for inflicting swift punishments to the school and university students who willingly participated in national revolutionary movements. Criminal jurisprudence went for a toss when JWF Dumergue, the Chief Secretary of Madras, appealed to make the parents watch the flogging of their convicted children. His demonstration proved no point on establishing a general deterrence to the public. The social and political reformers also paid no heed to its adverse effect on the child’s post-traumatic transition.

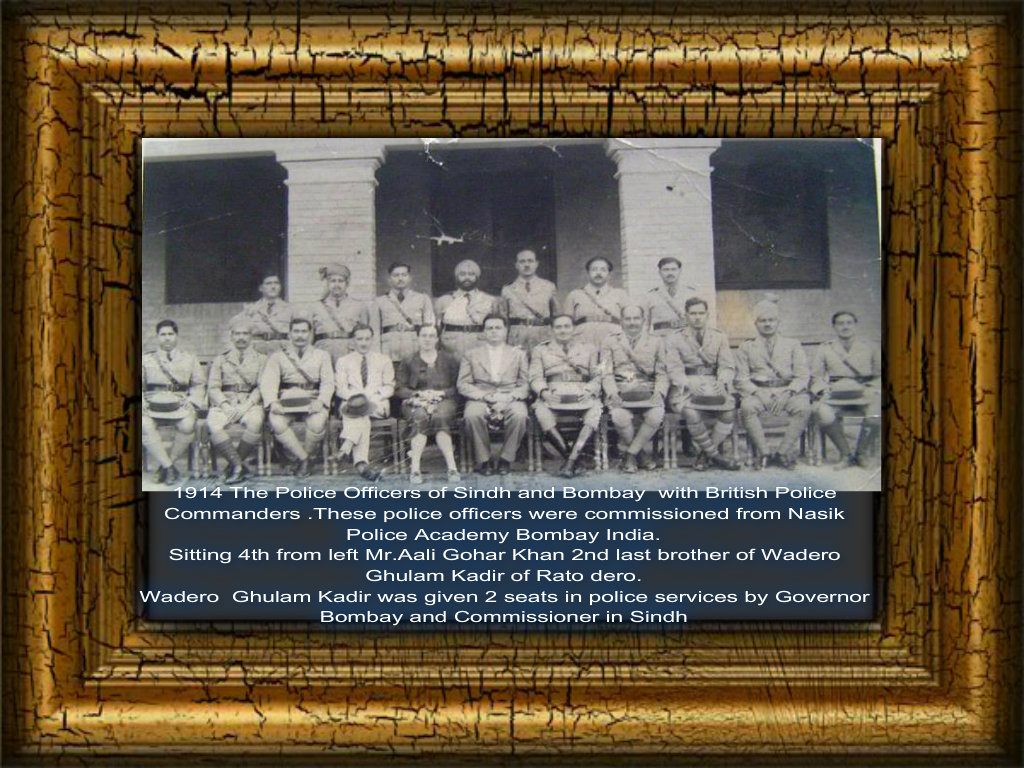

Police officers of Sindh and Bombay with British Police Commanders (1914)

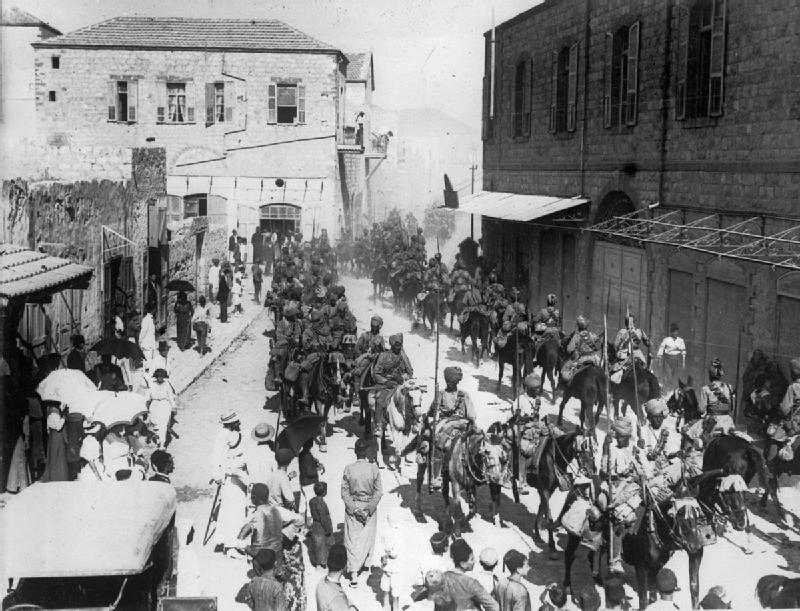

Native army men also fell under the unsparing hand of a similar law provided by the Indian Army’s disciplinary protocols. Though the use of corporal punishment in the Army increased during the World War I, its conclusion witnessed the abolition of whipping as a punishment in the year 1920, giving away an old trend persistently used by the Mughals upon their defaulting soldiers.

To one’s relief, the law did not apply to women and also to those sentenced to capital punishment. People committed to imprisonment for more than 5 years were also often spared from lashes at the discretion of the magistrate. It also exempted the offenders above the age of 48 on the grounds of seniority. At many provincial legislative assemblies, the number of lashes was decided not to exceed 30 and were subject to conditions like- mandatory approval and presence of a medical officer before carrying out the punishment.

There were also a few in the colonial lot who felt for the victims. Frederick Broom Napier, a famous colonial administrator, condemned the punishment by calling it ineffective and morally indefensible. The liberal party’s Member of Parliament, Henry Cotton, also slammed the abuse of whipping in India.

Indian Lancers

But the spirit rarely followed the letter of the law. Detailed discussions in the legislative assemblies brought a range of crimes punishable under the whipping act, but awarding whipping to a rape accused was rather mild, given the professed standards of Pax Britannica. Gender distinction on paper forced no restrictions on the use of lashes as both men and women working at the tea gardens were mercilessly flogged side by side, and rattan remained to be the sole instrument of oppression throughout the freedom struggle.

Abolition of the Whipping Act in the year 1955 has failed to dissuade the police from its misuse. Though written off from the books, the lathi still has its secure place in police stations, alongside new instruments like PVC pipes. The unbridled use of archaic punishments and lack of guidelines to monitor the policing authority has exposed the inability and unpreparedness of the Indian Government in confounding circumstances like pandemics.

In the mad excitement of the lockdown, many honest citizens and uninformed labour have become the victim of this colonial legacy hardcoded in the genes of today’s policing authorities. The fear of the lathi kept many needy away from vital necessities. While fear underlines the work of establishing general deterrence, such fear also breeds vengeance and often backfires. Unjust thrashing only makes people grieve upon their misery and nurse sullen resentment.

Whip seller. Courtesy: Wellcome Collection

The recent lethal attacks on police confirm the exasperated public sentiments. While other nations have found innovative ways to keep people inside during the lockdown, India failed to revamp its undermined reputation on an international pedestal. The damage hasn’t reached the level of beyond repairs yet. The answers to such problems are often in the plain sight but ignored. Economic sanctions, revocation of driving licence, impounding of the vehicles, and community service appears way more effective in contrast to lathi charge.

However, every coin has two sides. Police officers in India work through the day and into the night to control a crowd which at times may become unruly. The good deeds by the policemen during the lockdown exceed the negativity reported across the country. The only lesson which deserves our attention is that of empathy and how not to repeat the mistakes from our past.